Hey y’all,

I first heard about Annie Murphy Paul’s The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain when I heard her on The Ezra Klein Show. I’ve since read the book and started reading Paul’s newsletter, The Science of Creativity.

I wrote to you last year about thinking on the page, but I wanted to write a little bit more about The Extended Mind, because I found that it gave me an interesting framework for thinking about so much of the creative work I do.

Our culture tends to think about thinking as happening mostly in our heads, and that all we need to do to think better is sit down, distraction-free, and concentrate. You know, like Rodin’s The Thinker:

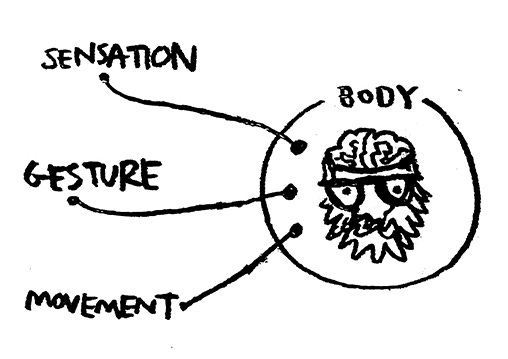

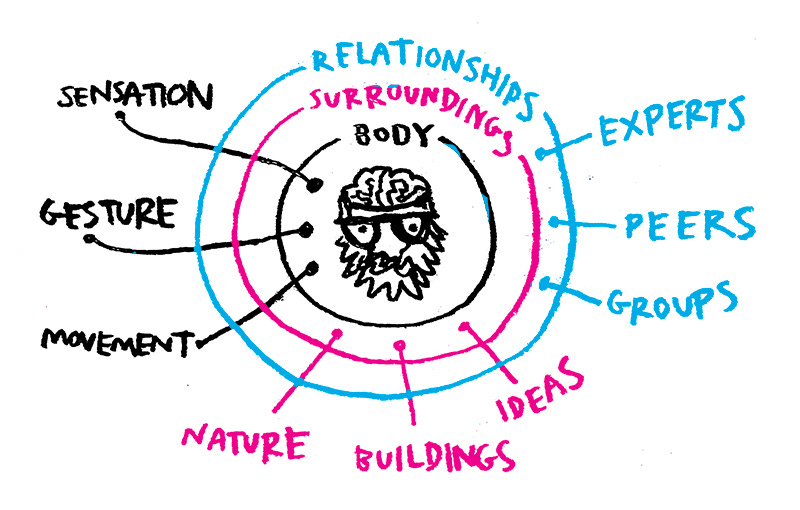

Paul calls this “brainbound” thinking. Her message is that we actually do some of our best thinking when we’re moving our bodies, navigating our surroundings, and interacting with other people. This message has profound lessons for our schools and workplaces. When I was reading the book, I imagined these three categories — body, surroundings, other people — as concentric circles that radiated outwards.

With the body, we can think with sensations, gestures, and movement.

Your sensations are your gut feelings, your goosebumps, the hairs standing up on the back of your neck, etc. It’s your body knowing things way before your brain does. A good way to get in touch with these sensations is to practice meditation: to learn to sit and listen to your body and what it’s trying to tell you.

Gestures are ways we use our hands. Paul focuses on the power of gestures while speaking (see: Bruno Munari’s book Speak Italian) but I thought a lot about drawing and sewing and playing music and writing by hand.

Exercise — moving the body — is a good trick to getting the mind moving. Paul points out “the words we use when we can’t seem to muster an original idea — we’re ‘stuck,’ ‘in a rut’ — and those we reach for when we feel visited by the muse. Then we’re ‘on a roll,’ our thoughts are ‘flowing.’”

In our surroundings, we can think in nature, with built spaces, and the space of ideas.

As for nature, simply getting outdoors seems to do wonders. (“Get out now.”)

Our built spaces are best when they act as a kind of external brain, with all our stuff surrounding us. We need walls to keep people out, our materials at hand, and special objects to make us feel at home. (I thought so much about this when building my dream studio. Here’s a peek inside.)

The space of ideas seems abstract, but it’s everything we talk so much about in this newsletter: getting ideas on paper so you can really see them, journaling, taking notes, making a map of your mind, etc. (It was from this chapter that I quoted the story of Darwin learning to journal.)

Finally, when thinking with our relationships, we have experts, peers, and groups.

We imitate experts, apprenticing ourselves to the good work that’s come before us.

Our peers give us a chance to teach and learn from each other. When we try to share what we think we know with others, we find out what we really know and don’t know. (I wonder where children fit in this scheme — I would actually create a whole other category for them. Perhaps that’s a book I should write: Thinking With Children.)

As for groups, this I’m the least personally sold on, but then again, I am a big believer in scenius.

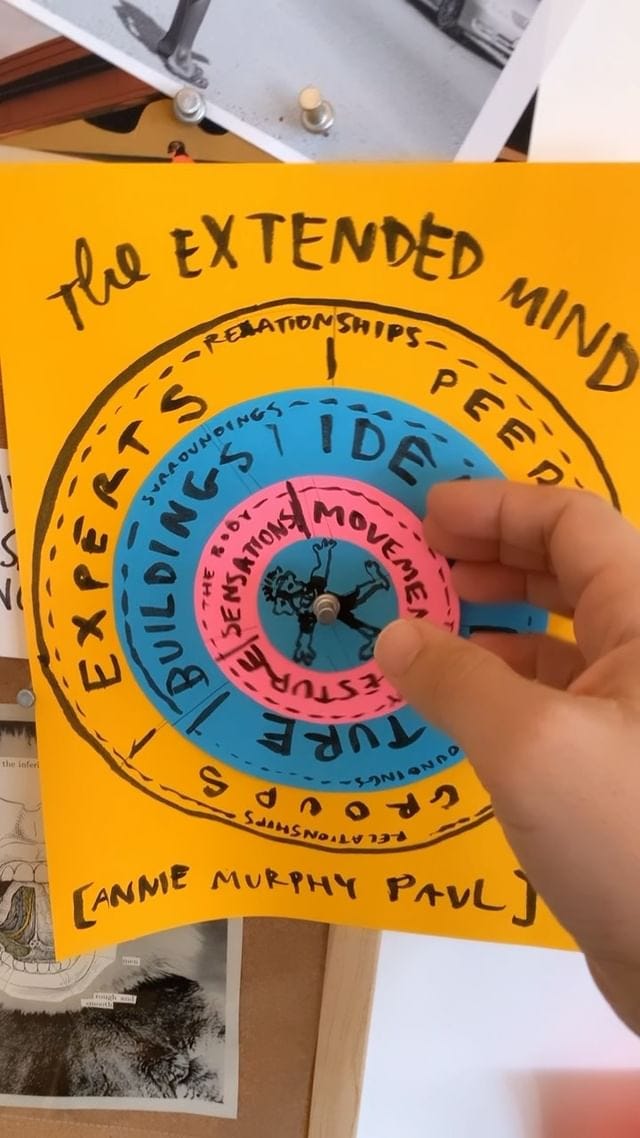

While I was reading, I was inspired to make a volvelle that has spinning circles so I could spin it around and line up different combinations of these ways of thinking.

For example, if you line up movement and nature, you basically have a solo bike ride, which is great for clearing your head. If you add peers to the mix, you’ve got my weekly bike rides with my bike gang. A lot of good thinking happens on those rides.

Gesture + ideas + experts = reading with a pencil.

Etc.

Two books I thought a lot about when reading: David Allen’s Getting Things Done, which is so much about getting things out of your head so you can do something with them, and Alan Jacobs’ How To Think, which makes the case that “Thinking is necessarily, thoroughly, and wonderfully social.”

If you want to dive deeper on the theory behind these subjects, look up “embodied cognition.”

Now I want to hear from you all: How do you get out of your head so you can think? Tell us in the comments:

xoxo,

Austin

My comment relates to "thinking with children."I teach art workshops on drawing and watercolor and journal keeping. For years I taught these workshops in the local schools, mostly to second graders. When I first began teaching these workshops, I experienced them as a big interruption to my own creative endeavors. Then I had the breakthrough to incorporate my own art into the teaching process. I would show the students the beginnings of a painting. (They would ooh and ahh, but I would point out the places where I didn't feel satisfied or felt it was unfinished.) I'd bring the piece back the next week and show them what I had done to push the drawing forward. This accomplished a number of things. First, it transformed my relationship with the kids from being the teacher/expert to being a colleague, an equal. I was actually demonstrating the advice I was giving to the kids--work with what you have; you can't erase your "mistakes" but you can change them. Also, that while you don't know it from a finished piece, my drawings are never what I first envisioned when I'm about to start. There's the idea and a blank piece of paper. Then there are the first marks, and then you have to put aside your vision and work with what is on the page. And you only get one piece of paper. You can turn it over and start again if you think you've made a mistake, but that's the only sheet of paper I'm going to give you (we worked on artist-quality watercolor and drawing paper which would hold up with lots of reworking and was too expensive to waste.) My teaching workshops began to feed my own creative process rather than interrupt it and I learned to take my own advice in a deeper way. And I often found the student's art to be inspiring and innovative in ways that were unexpected. As I helped them see their own work, not in terms of what they had wanted to do, but in terms of what they had done, that was very exciting and interesting, I learned to see my own work in more objective terms. I certainly learned as much from the kids as they learned from me. I've taught the same workshops to adults, and I find that working with kids results in many ideas that adults don't generate, mostly because they already think they know what art should be, while kids are more open to the process itself.

I love mind maps. One thing that helps me even more is a *moveable* mind map. I write my central question or idea in the center of a large sheet of drawing paper. Then I’ll take small pieces of paper or Post-it notes and write individual concepts on those. I can arrange and rearrange the small pieces around the central idea, adding and subtracting, until my thinking becomes clearer. Something about using my hands to move the pieces around helps me think.