Thinking on the page

Thoughts on “the extended mind” and a few peeks into my current notebook

Hey y’all,

One of the great leaps I took in my work was when I internalized the idea that writing and drawing, at their best, are about thinking on the page.

The mistake I used to make was thinking that I had to have an idea in my head before I started making marks on the page. More often than not, it’s the other way around: making marks on the page gives me an idea, which I then follow by making more marks, which gives me more ideas, and so forth.

Thinking this way is about setting up a loop between head and eye and hand and materials.

(You only need to watch Ralph Steadman draw to see an extreme version of what I’m talking about.)

Speaking of loops: I am repeating myself. Here’s what I wrote to you a few weeks ago:

Drawing isn’t a one-way street from your brain to your hand. It’s a two-way street BETWEEN them. Your hand making the line tells your brain as much as your brain tells your hand. You might try to “run a line around your think,” but pretty soon the line bolts and gets away from you.

Endless frustration for artists of all ages comes from thinking drawing is just about getting down what you see with your eye or in your mind’s eye. The drawing emerges from the friction between what’s in the mind’s eye and the materials — you can struggle with it or you can dance.

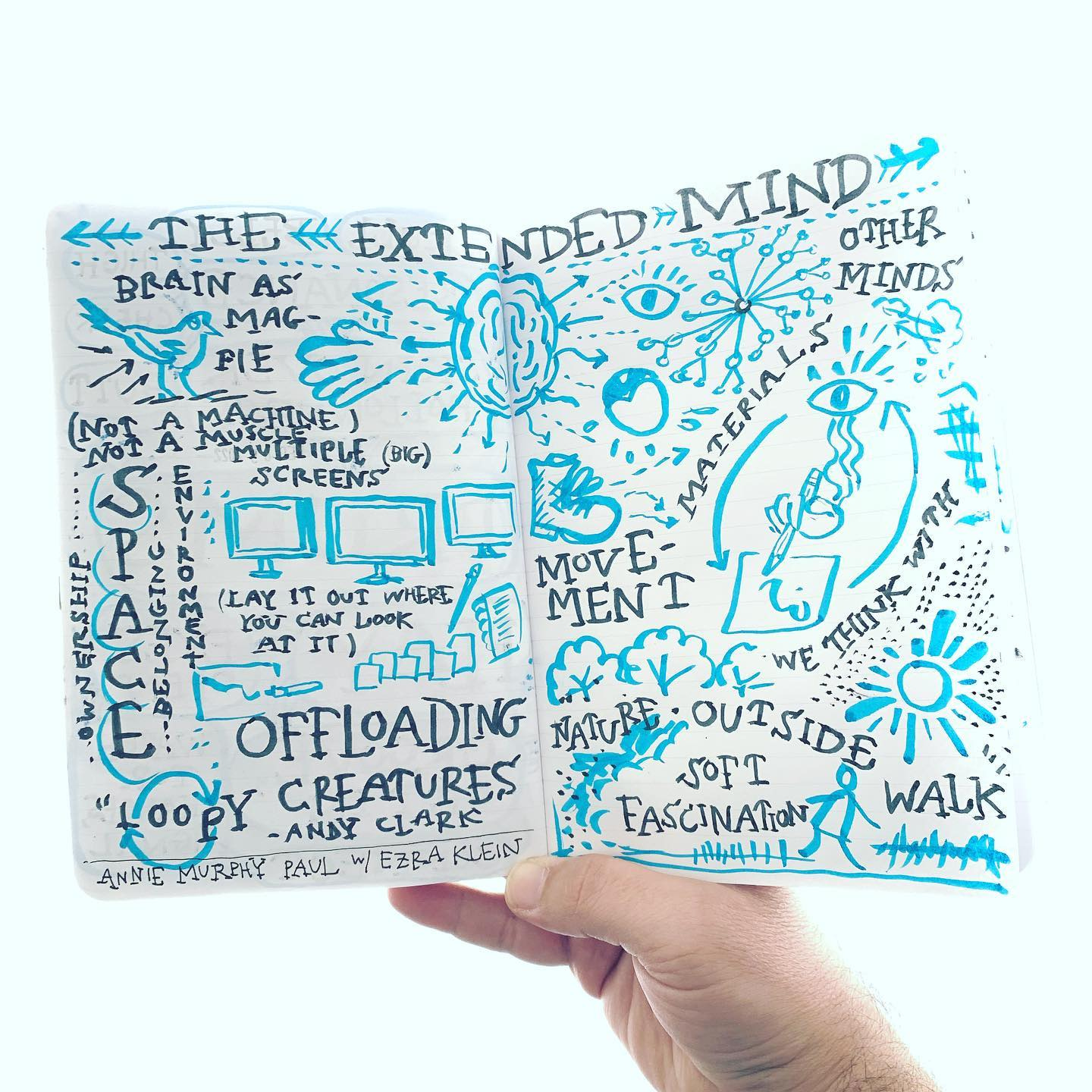

I started thinking about all of this again after listening to this conversation between Ezra Klein and Annie Murphy Paul about her book, The Extended Mind: The Power of Thinking Outside the Brain:

I write a lot in the book about how artists and designers and people who swear by the pencil and the conversation that happens between pencil and hand and eye and paper that, again, it’s kind of a misunderstanding to think that the brain conceptualizes an idea or an image and then tells the hand how to execute it and then it’s done. That’s a very computer-like idea of how work happens. Instead, artists and designers find that it’s much more of an iterative process where they draw something. They make a mark, and then the mark reminds them of something. And they add another mark. And it’s a conversation, again, between hand and eye and paper and pencil. And I think the materials we use to do our thinking with, our external outside the brain thinking, can make a big difference in terms of what kinds of thoughts we’re able to have.

I want to show you some examples of how this actually works for me.

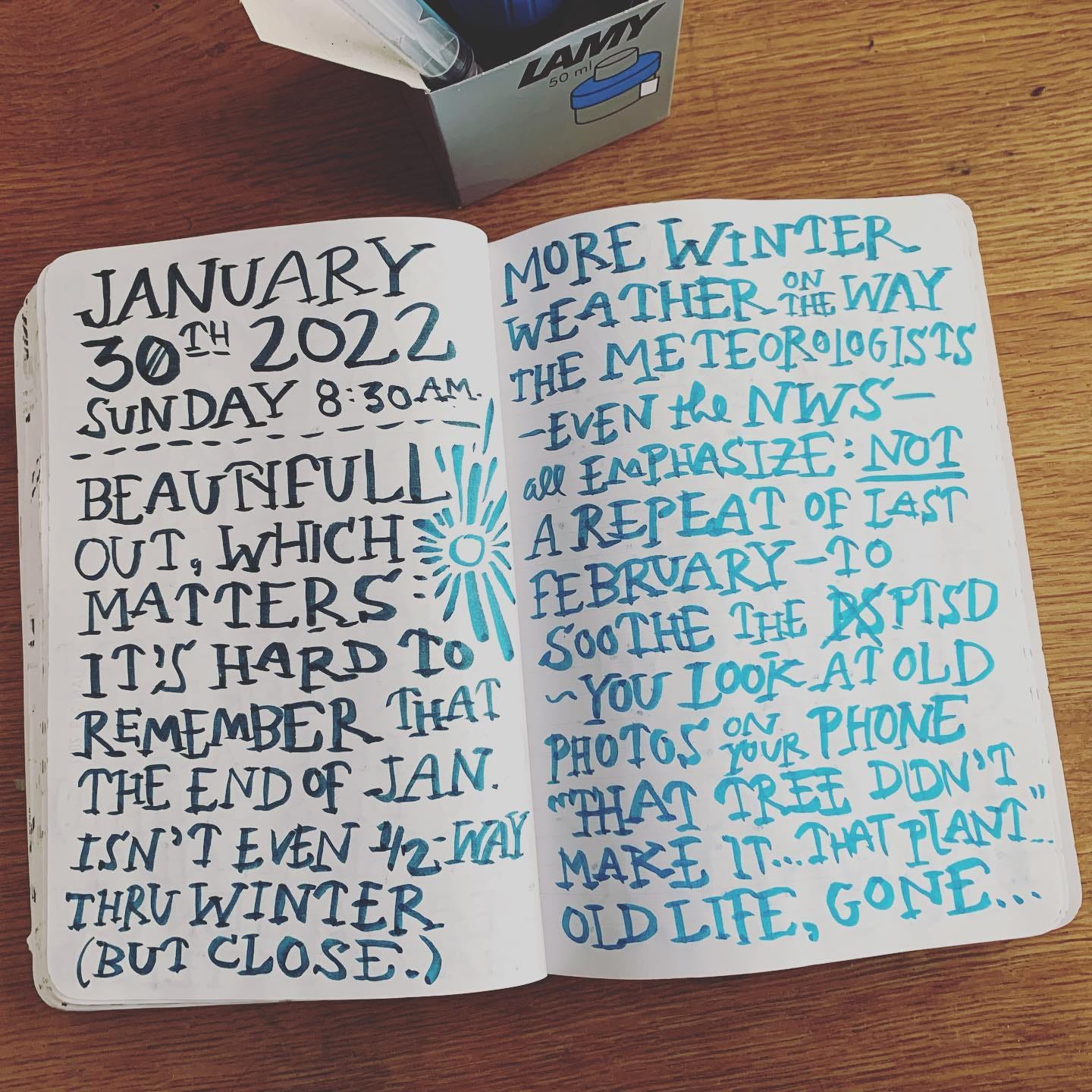

I bought some turquoise ink to refill one of my magic brush pens, and when I started writing with it, it still had a lot of black in the brush, which slowly turned lighter and lighter until the turquoise appeared, and provided me with a delightful metaphor:

Sometimes you just have to write your way out of the dark into the light.

I soon got to thinking about how I could use the black and blue brushes together…

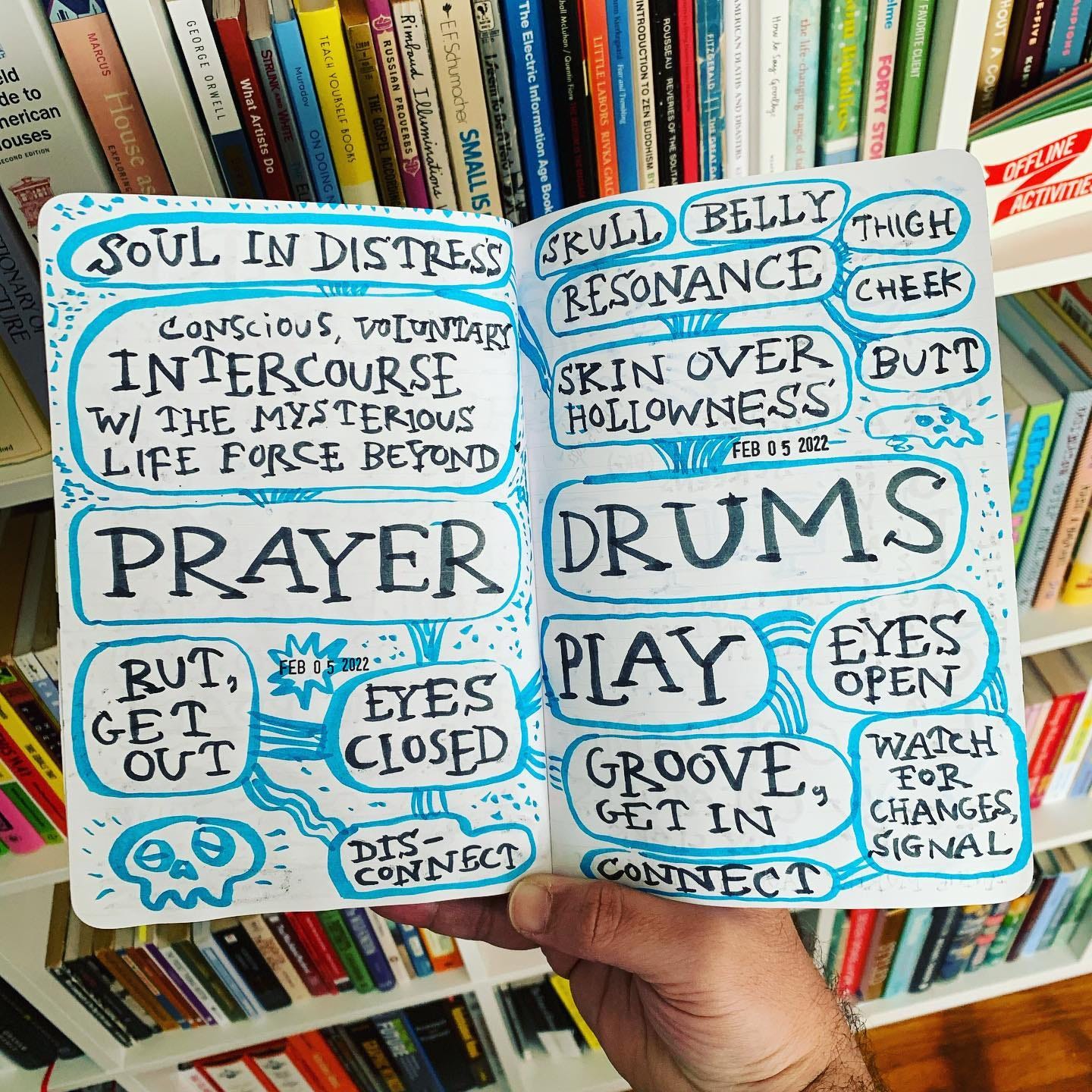

Above is an example of one of my mind maps: I started with the words “prayer” and “drums.” Then I copied a few phrases from William James’ The Varieties of Religious Experience and W.A. Mathieu’s The Listening Book and connected them with turquoise ink. (This gives my hand something to do while I’m thinking.) Suddenly I remembered a connection between playing and praying and then I thought about “groove” vs. “rut” and having your “eyes closed” vs. “eyes open.”

Doing this kind of map almost always leads me to ideas I don’t think I’d get from trying to write straight prose.

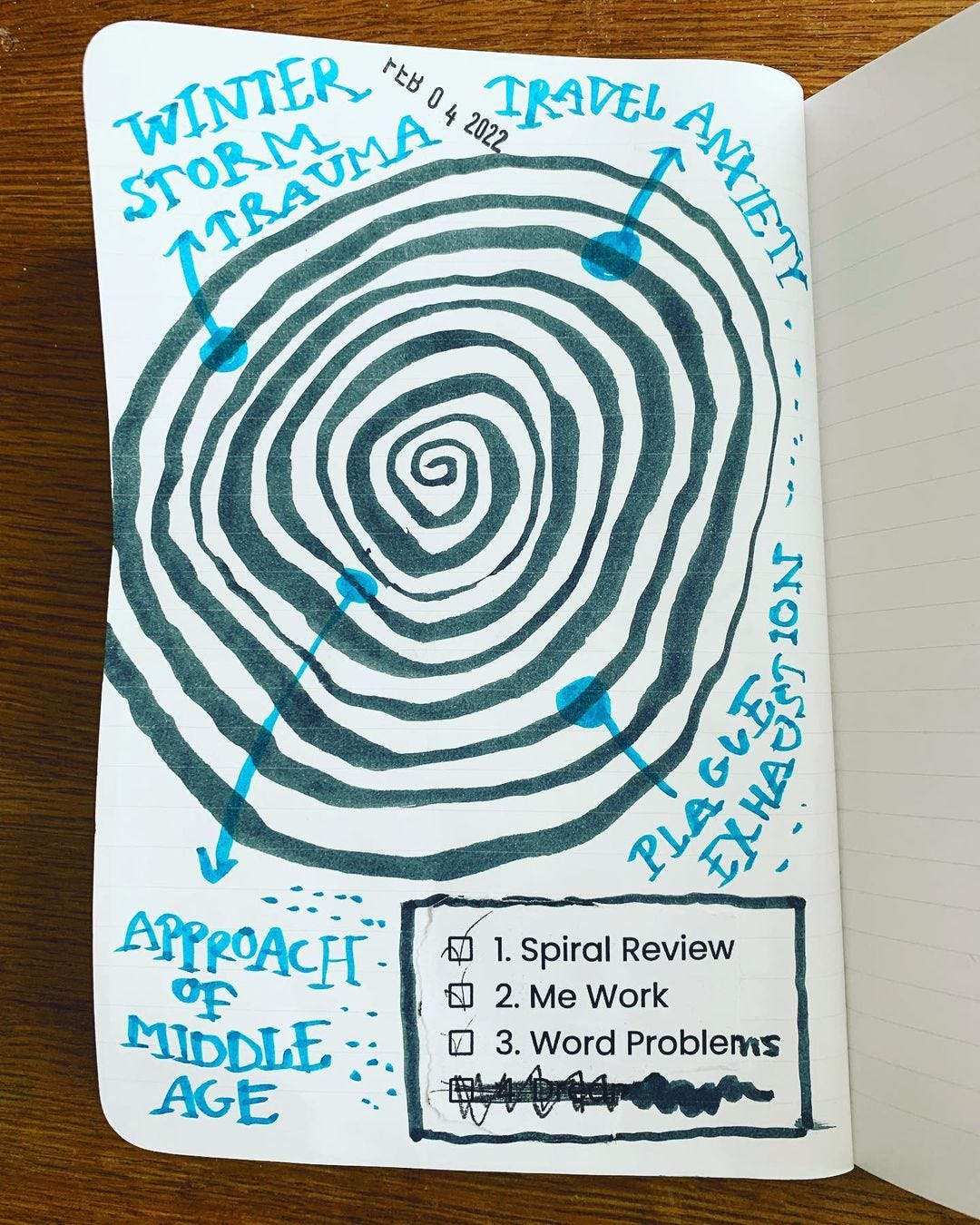

On this page, I pasted part of a worksheet that came home with my first grader — I found the items “Spiral review” and “Me Work” really funny together, so I drew a Lynda Barry spiral and annotated it with “Me Work” in turquoise. (My life is “word problems.”) Again, this wasn’t really pre-planned: it started with gluing one thing to another and then moving the brush.

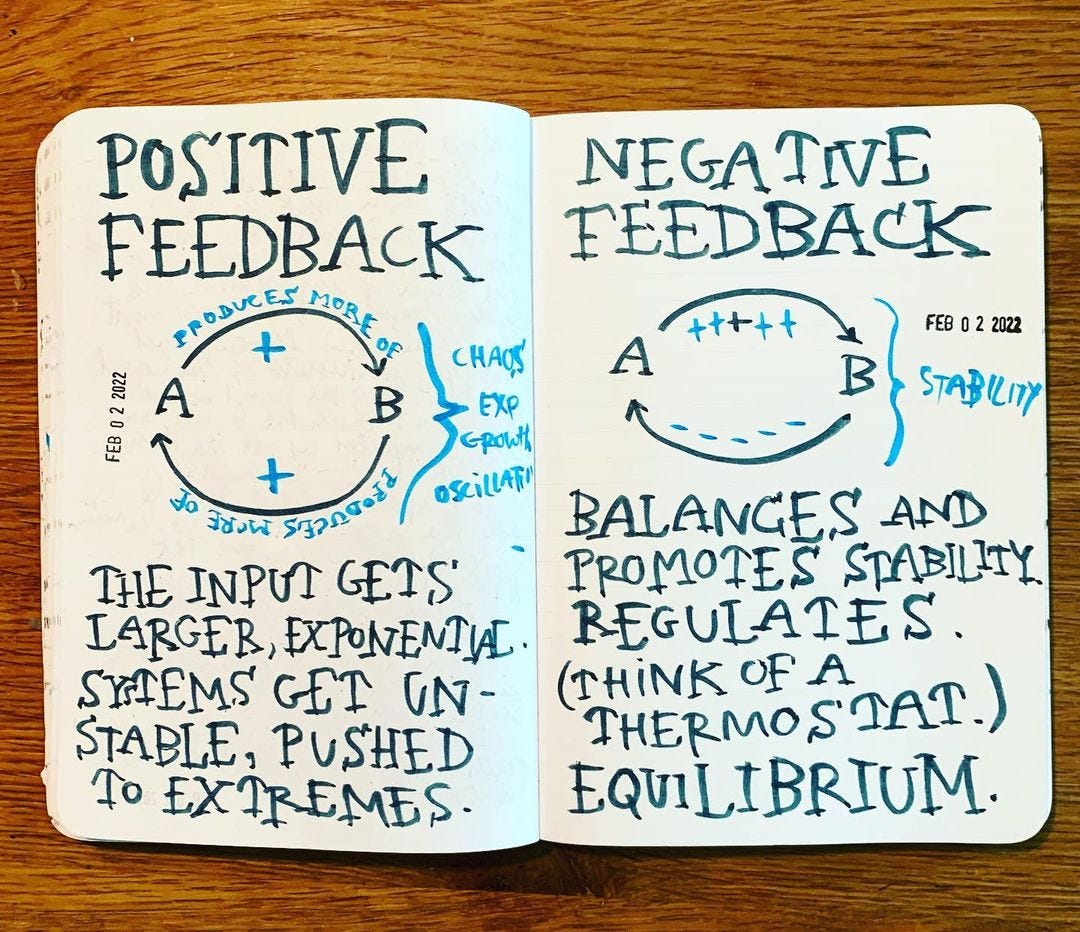

When I don’t know what to write or draw, I often use the diary as a way of working out or copying out by hand ideas that I’m trying to learn about. (Here, it was positive vs. negative feedback, which are tricky concepts, because positive feedback can be harmful and negative feedback helpful, depending on the context!)

What I’m trying to demonstrate here with these recent pages is that the majority of good thinking that I do happens on the page. I can think all I want in my head, but it’s only when I grapple with the ideas on the page that I can make something of them. The thinking happens mostly outside of my mind, or, rather, in a loop of outside and inside.

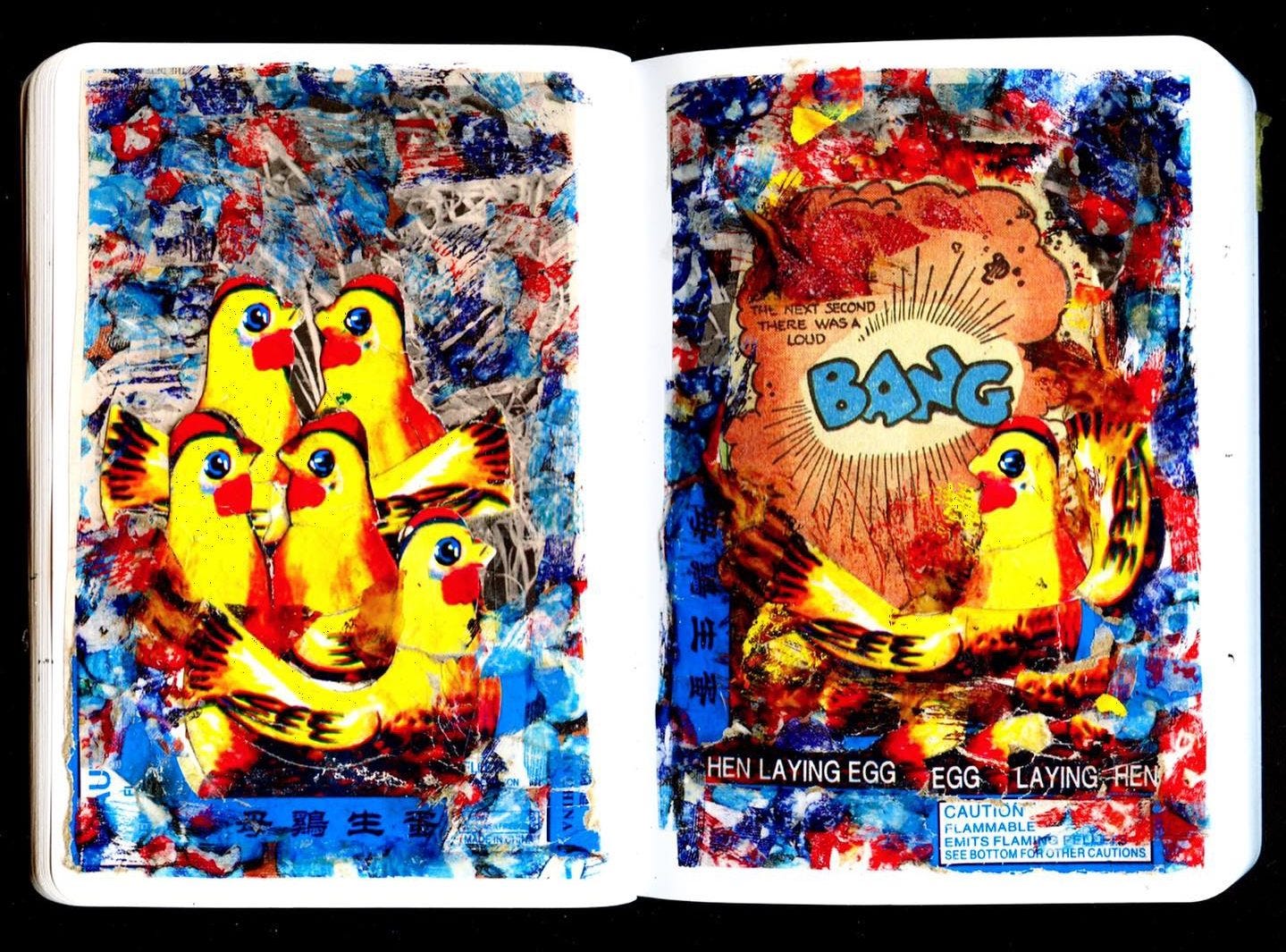

One of the “strange loops” that Hofstadter talked about was the “chicken or the egg” problem — which came first? For me, it’s neither: what comes first is the “nest egg,” the egg-looking object you put down in the nest to get the hen to lay her eggs next to it. Here’s what Thoreau wrote:

Each thought that is welcomed and recorded is a nest egg, by the side of which more will be laid. Thoughts accidentally thrown together become a frame in which more may be developed and exhibited… Having by chance recorded a few disconnected thoughts and brought them into juxtaposition, they suggest a whole new field in which it was possible to labor and to think. Thought begat thought.

Or, in my case: mark begets thought.

That is my advice for this week: If you want to think, sit down and start making marks on the page. The thoughts will come.

What do you do to get your thoughts going? Let us know in the comments:

xoxo,

Austin

Excellent reminder. I frequently write down a single word, and it leads to both memories and new thoughts. Writing the word 'Gratitude' took me back to WWII, and our dinner table. We were a family that said a blessing before and after a meal. Some days our after meal blessing went like this: We thank the Lord for all we've had. For a little bit more we'd have been very glad. But as the times are very bad, we thank the Lord for all we've had." Imbued each of us with a sense of gratitude - which lasted a lifetime.

I do very similar things. I have been journaling daily since January, and it’s almost like once I put some marks to the paper, ideas start to come. They come so quickly sometimes I don’t even think where they are leading me. That’s what I avoid (unconsciously) in the initial stages of drawing - thinking. Once I feel this is going somewhere, then I tend to think more rationally or connect ideas more consciously. For example, I usually start with my pen moving in random (but slow) squiggly kind of directions, suddenly i think oh maybe I this can be a map, I play more, and suddenly that starts becoming a face, so I just go with it. I am purely drawing some forms, then not thinking initially helps.