Hey y’all,

There were so many great responses to my question, “Is there a tool that makes you feel closer to somebody?” I loved thinking about Emily using the pair of scissors that got in the 6th grade — “not too tight, too loose, too long” — and how she says they make her feel close to the kid she used to be.

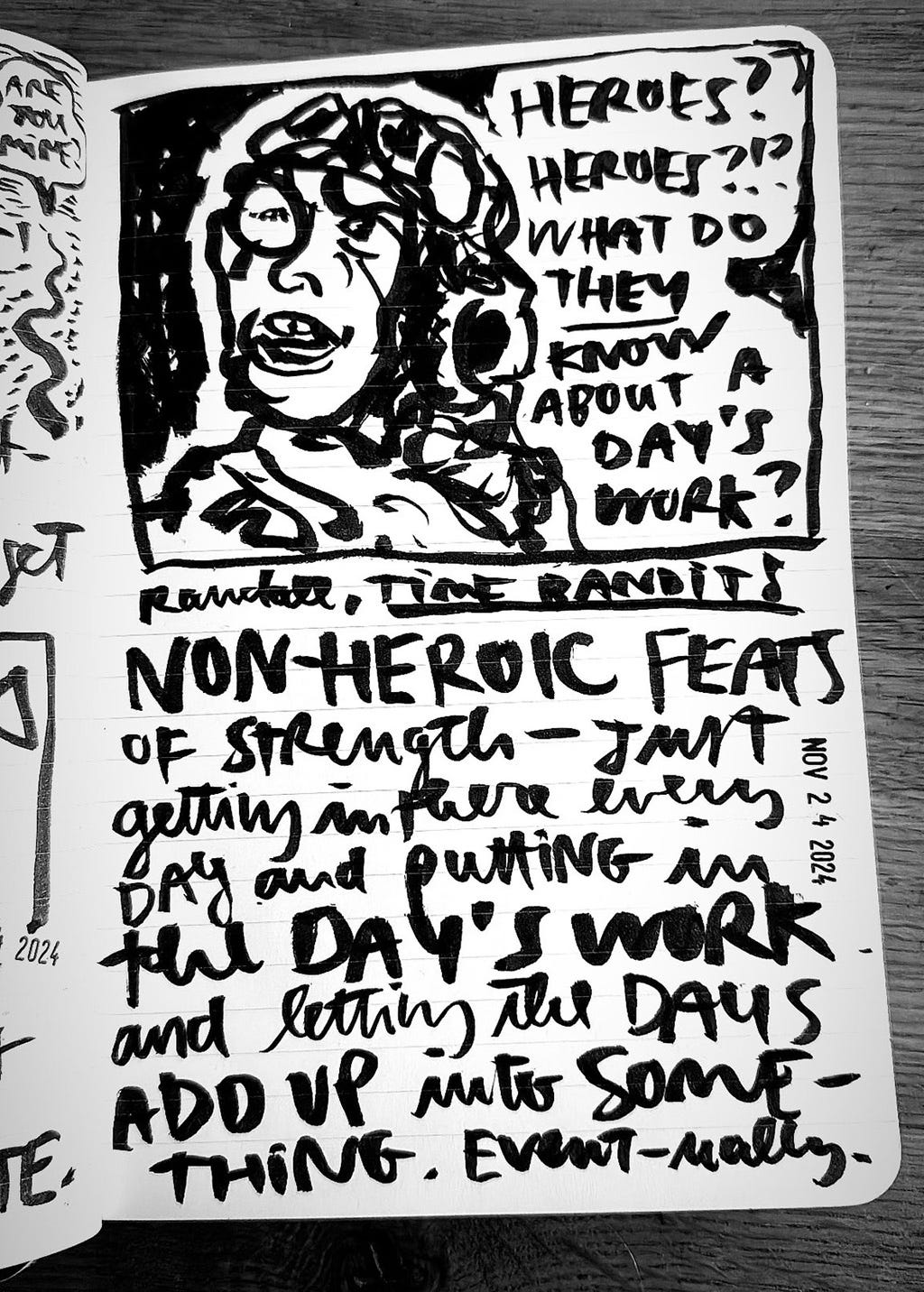

It got me thinking about keeping a diary, and how re-reading mine helps me stay in touch with previous versions of myself.

“I think we are well advised to keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be,” is how Joan Didion put it. “We forget all too soon the things we thought we could never forget.”

I finished a diary a few days ago and flipped back to the beginning and started reading the entries from when I started it back in August while vacationing on Oahu. A lot has happened since then — I sold my book, the boys went back to school, summer turned to fall, etc.

I made one of my goofy weigh-out videos to mark the occasion:

I recently came across an interesting passage on diary-keeping from Walter Ong’s Orality and Literacy. Ong was interested in the difference between talking and writing.

When we speak to somebody, we know who we’re addressing, we know the context we’re in, what the room is like, we can read how the person we’re speaking to is reacting, and we modify what we’re saying to suit the situation.

When we’re writing, Ong points out, we have none of this “extratextual context.” This is what makes writing so difficult. All we really have — the writer and the reader — is the words that are on the page.

Even if we try to write a letter to one specific person, Ong thinks that “the writer’s audience is always a fiction.”

Even in writing to a close friend I have to fictionalize a mood for him, to which he is expected to conform. The reader must also fictionalize the writer. When my friend reads my letter, I may be in an entirely different frame of mind from when I wrote it. Indeed, I may very well be dead. For a text to convey its message, it does not matter whether the author is dead or alive. Most books extant today were written by persons now dead. Spoken utterance comes only from the living.

Then he writes about keeping a diary:

Even in a personal diary addressed to myself I must fictionalize the addressee. Indeed, the diary demands, in a way, the maximum fictionalizing of the utterer and the addressee. Writing is always a kind of imitation talking, and in a diary I therefore am pretending that I am talking to myself. But I never really talk this way to myself. Nor could I without writing or indeed without print. The personal diary is a very late literary form, in effect unknown until the seventeenth century (Boerner 1969). The kind of verbalized solipsistic reveries it implies are a product of consciousness as shaped by print culture. And for which self am I writing? Myself today? As I think I will be ten years from now? As I hope I will be? For myself as I imagine myself or hope others may imagine me? Questions such as this can and do fill diary writers with anxieties and often enough lead to discontinuation of diaries. The diarist can no longer live with his or her fiction.

Who am I writing to in my diary? It depends on what’s happening.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Austin Kleon to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.