Maps of scenius

The networks of creativity

Hey y’all,

I have written to you several times about “scenius” — a portmanteau Brian Eno coined to describe the communal origin of creativity that arises out of a scene. Scenius is the backbone of my book Show Your Work! and is usually the starting point of my talks. It is my belief that most people who want to be creative would be served best not by worrying about genius but by trying to create or join a scenius. (More here.)

Something I don’t spend a lot of time on is listing or describing particular examples of scenius. Doing so would be its own full-time job, as once you go looking for scenius, you start to see it everywhere.

Just this week I was made aware of “The Diane Fink School,” named after the landlord of the NYC building at 368 Broadway where Greta Gerwig, Lena Dunham, the Safdie Brothers, the Neistat Brothers, and other filmmakers started their careers:

If you watch that video, or listen to Van Neistat describing those days, you can detect some of the scenius-nurturing factors that Kevin Kelly laid out in his 2008 post:

mutual appreciation and friendly competition

the rapid exchange of tools and techniques

the network effects of success (cf: “shine theory”)

There are times and places in which the conditions are ripe for these kinds of sceniuses to appear. On a large scale, you have ancient Athens, or Renaissance Florence, or Elizabethan England. On a smaller scale, you have Gertrude Stein’s salons or Max Planck’s house parties. On an even smaller scale, I think even a single household can be a scenius, like The Wyeth Family.

One thing worth doing is to re-map “geniuses” and locate them within a scenius. Emily Dickinson, for example, is famously thought of as a recluse, but she was really a “networked recluse.” (More recently, the lone genius myth of the painter Hilma af Klint has been questioned.)

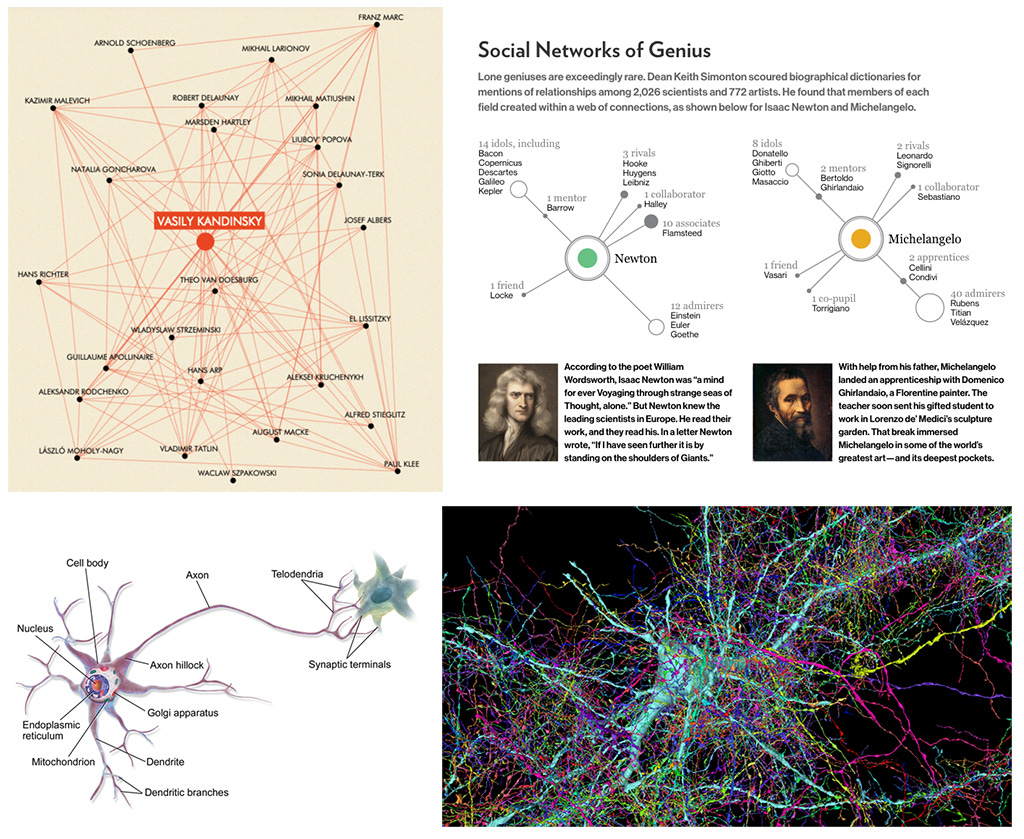

I like to collect maps of scenius that appear here and there in my reading. It always strikes me how much they look like maps I’ve seen of neurons in the brain:

Innovations, large or small, do not require heroic geniuses any more than your thoughts hinge on a particular neuron. Rather, just as thoughts are an emergent property of neurons firing in our neural networks, innovations arise as an emergent consequence of our species’ psychology applied within our societies and social networks.

That’s how researchers Michael Muthukrishna and Joseph Henrich put it in a paper about how our social networks act as collective brains. According to them, the sources of innovation — serendipity, recombination, and incremental improvement — seem to arise in environments of interconnectedness.

Having a lot of brains connected to other brains boosts our collective creativity, but what about our individual creativity?

Since living through a global pandemic, I’ve been thinking about how much the scenius maps resemble a virus, or this map which ran in Harper’s in 2005. (One of my favorite maps of all-time — I love looking at it and imagining the stories.)

The writer Elisa Gabbert has pointed out that influence and influenza have the same etymology. In a very real sense, the conditions ripe for influence are also the conditions for influenza — ideas spread like the plague! (Ask me how many times my kids have been home sick from school in just the past five weeks.)

People go on artist retreats the same way they leave the city to get away from an outbreak. As I wrote in Keep Going:

Creativity is about connection—you must be connected to others in order to be inspired and share your own work—but it is also about disconnection. You must retreat from the world long enough to think, practice your art, and bring forth something worth sharing with others. You must play a little hide-and-seek in order to produce something worth being found.

This game of hide-and-seek is one in which you sort of bounce back and forth between the poles of genius and scenius — a cycle of seeking out inspiration, turning within to create, and then showing your work.

One heartening thing I’ve seen in the decade since I’ve been writing about scenius is a wealth of articles and books and movies that have a more collective take on creative work. (The above book covers are just a sampling that comes to mind — music, for example, is a more collaborative and social medium, so there are a bunch of books about individual music scenes. Not shown is an older book, one of my all-time favorites about making something happen where nothing is happening: Our Band Could Be Your Life.)

The more we’re exposed to scenius the more we can learn how to nurture sceniuses of our own. So now I’d like to hear from you: What are some of your favorite examples of scenius? Tell us in the comments:

xoxo,

Austin

I got to be part of a wildly creative scenius of several dozen families who homeschooled our kids back in the 90s and 2010s in a town in NC that had a great public school system. The reason this group of folks decided to homeschool was just simply because we wanted to spend more time with our kids as they grew up. And we all homeschooled in different ways, different philosophies (unschooling was common). Thursdays we would meet at a rotating local park all day. There was absolutely no agenda. The kids would play while we parents hung out together in a big circle of lawn chairs. A lot of the parents were writers and artists. We just hung out and sketched or talked or knitted. It was very relaxed and sort of tribal. The only requirement to be part of the group: Kindness. In fact, the group couldn’t even define itself-- we called ourselves “a fluid possibility.” The ideas that came from that scenius were endlessly creative. One 10 year old girl organized a big group of other kids to put on full Shakespeare plays every summer. Bands formed and still exist. When kind, creative people get together, something great it’s bound to happen. It’s inevitable like a virus or a snowflake, things just start sticking together.

tbh i have had a challenging time finding my scenius, finding any scenius - i live in hamilton ontario canada and there is the "cool kids" art group who have a thin outer shell of welcome hiding a concrete bunker of you can't play with us and a bunch of lone spirits (of which i am one) that occasionally bump off each other randomly but are yet to congeal into a mass (woo boy this is a mess of words but i hope someone will understand) - i crave a scenius and before anyone suggests i start a group i have tried that and honestly i need help and cannot manage this alone :(