A library of words

Discovering Roget’s Thesaurus

Hey y’all,

It felt like I spent the weekend in another century: Riding my bicycle, chopping wood, and obsessively reading Roget’s Thesaurus.

Let me explain that last item. I have always assumed — and maybe you have, too — that a thesaurus is just a synonym dictionary, the words arranged alphabetically with a list of synonyms and antonyms below. Somehow, every thesaurus I’d ever come across — even ones with “Roget” in the title! — had this alphabetic arrangement.

Because of this, it was easy for me to effectively ignore the thesaurus. If I needed a synonym or antonym, I’d just open an actual dictionary, or do a quick online search. This inclination was cemented as a habitual way of operating when I read John McPhee’s advice to skip the thesaurus and look up words you already know in the dictionary.

But on Friday, I was on the phone with a reporter, talking about ambition. You know how if you stare at a word long enough it starts looking like it’s spelled wrong? A-m-b-i-t-i-o-n. In the course of our conversation, “ambition” lost all meaning to me. I had to look it up in the dictionary just to remind myself what the word actually meant.

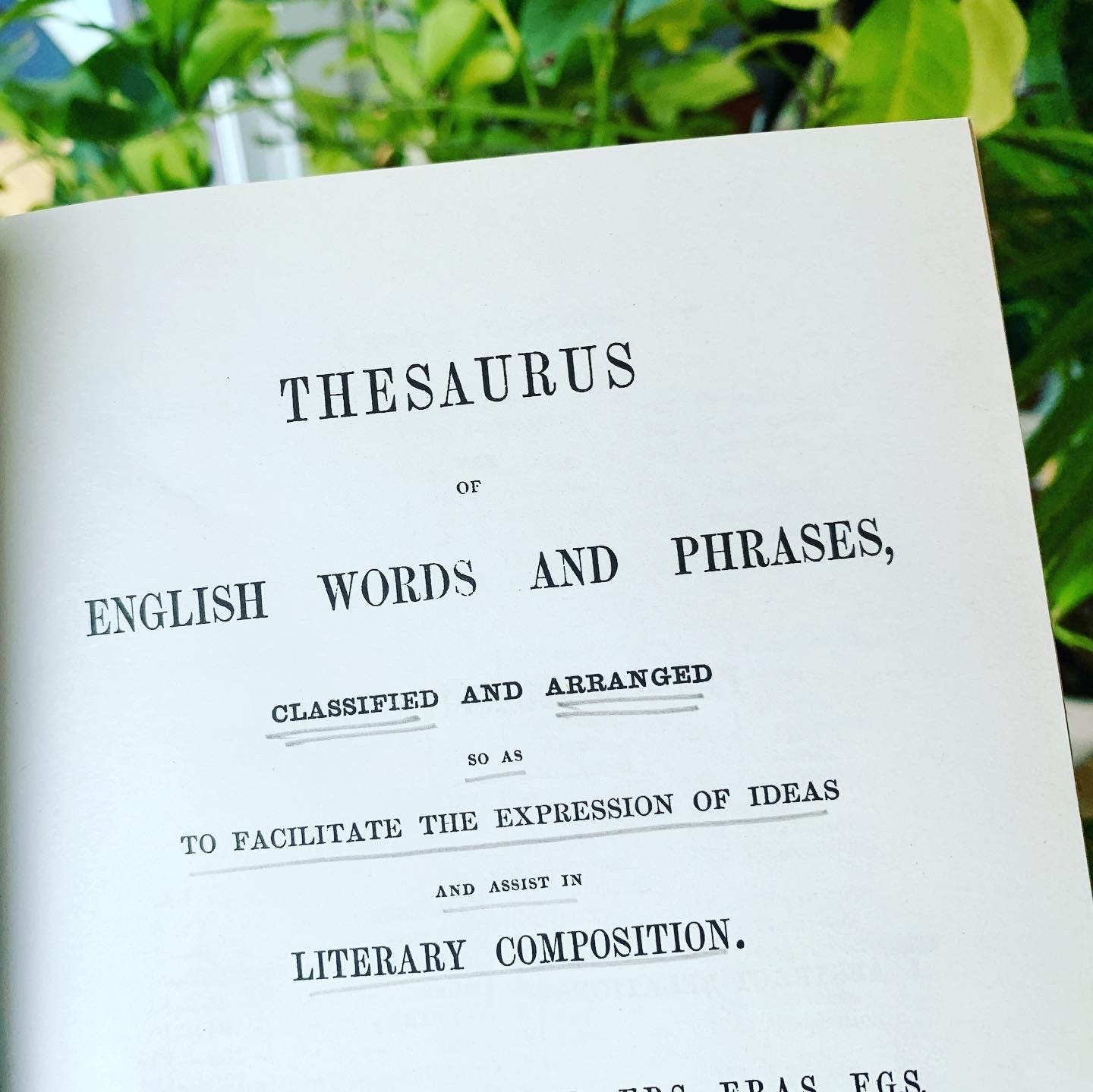

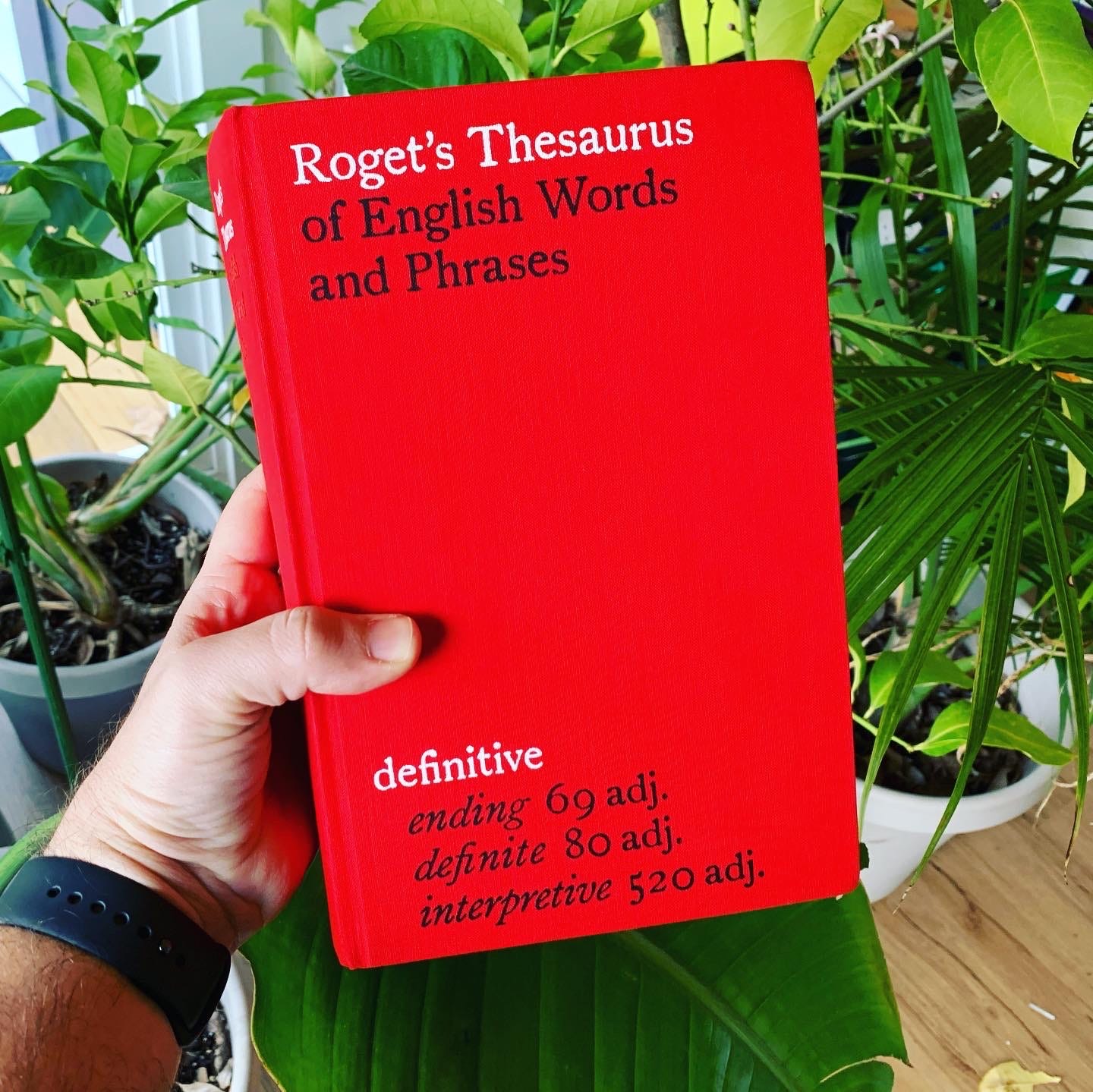

On the shelf next to my dictionary, I noticed my red 2019 Penguin UK edition of Roget’s Thesaurus of English Words and Phrases, a book I purchased on a whim and never actually cracked. I opened it, ready to search for “ambition,” and thought, What the hell is this?

It turns out that Roget‘s Thesaurus is not at all what I thought it was. It is weirder and much more interesting. In the words of Ted Gioia, “Roget's Thesaurus is an oddball philosophy of language masquerading as a reference book.”

Let’s go back to the beginning, because if you understand the man, you understand where his book came from. Peter Mark Roget (1779-1869) was a Victorian polymath: a doctor by trade, but he did all sorts of stuff: he was a consultant on pandemics, he wrote Encyclopedia Brittanica entries and a book about natural theology, he helped catalog several libraries, he invented the scale on the slide rule, and he may have written a paper that contributed to the birth of cinema. Oh, and he was also obsessed with chess problems.

The thing he is now most famous for — his thesaurus — was actually a side project he took up in retirement, in his seventies. His whole life he’d made lists as a way of soothing himself. He carried a notebook around with him and jotted down lists of related words and phrases to help him with his own writing and lecturing. He made his own personal thesaurus in his twenties, but in retirement he thought maybe it might be helpful to others, and after four years of work, he published the first edition of his Thesaurus (from the Greek word thēsauros, meaning “storehouse” or “treasure”) in 1852, overseeing new editions until he died in 1869. His son, John Lewis Roget, a lawyer, painter, and art critic, then took over the project.

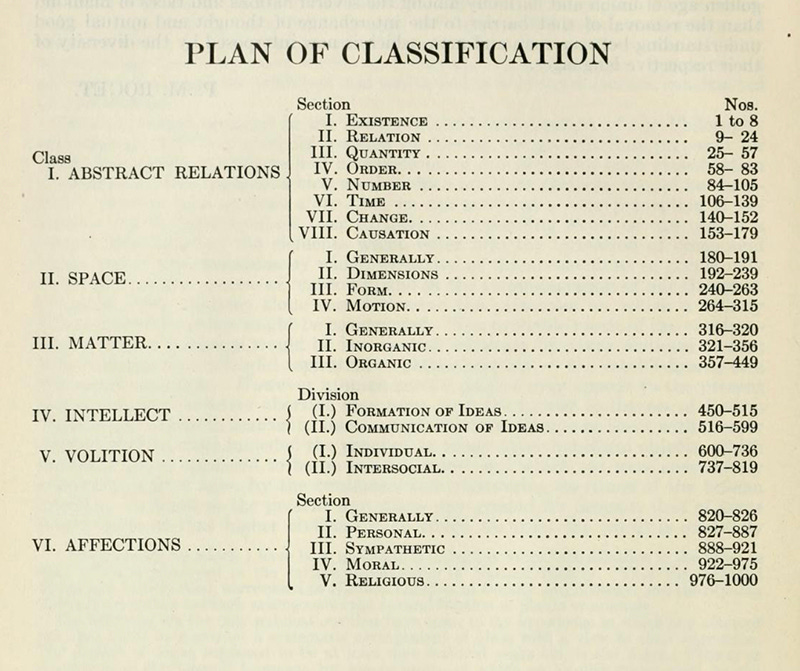

Roget, like many Victorians, was obsessed with order and classification. His hero was Carl Linnaeus, known as the father of modern taxonomy. Roget wanted to classify and organize words in the English language. This is the best way to understand Roget’s Thesaurus: it’s not just a book of words, it’s like a library of words.

When you go to the library, the books are not arranged in alphabetical order — they’re organized topically. In order to find a book in my local library, you have to look up the book in the catalog, note the Dewey Decimal Number, then find it on the shelf. The beauty of this system, and a major argument for physical browsing collections, is that when you find the book on the shelf, it will be surrounded by books on the similar subject. You may go looking for one particular book and while browsing you might find a better book or the book you didn’t even know you were looking for. This is the way a thesaurus is supposed to work.

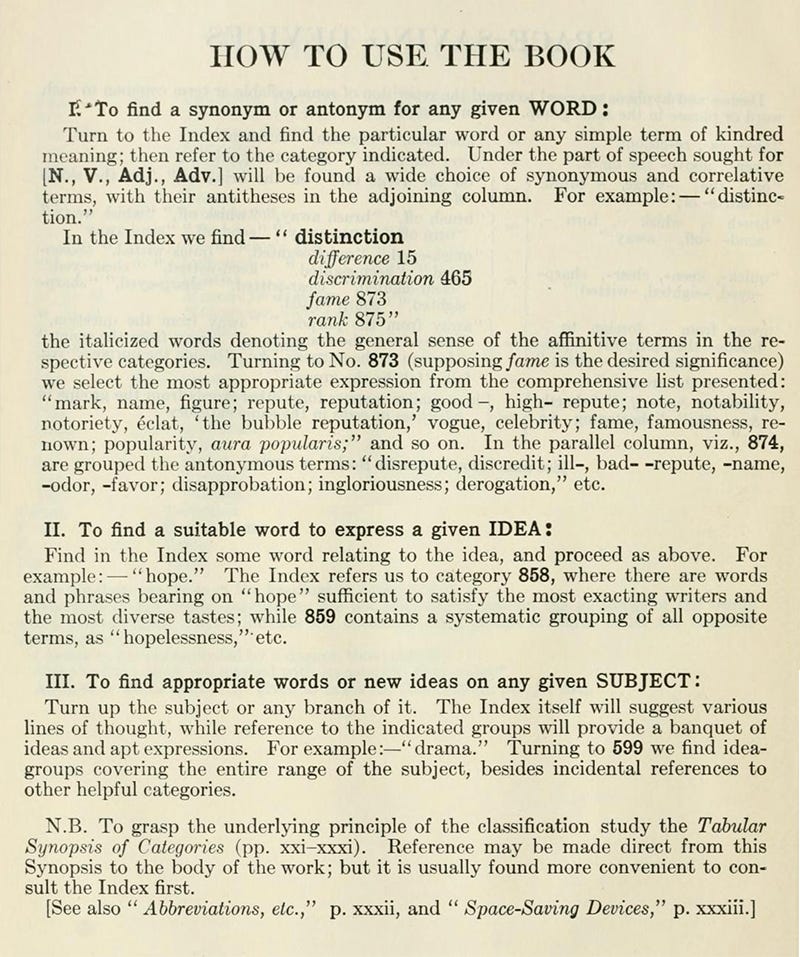

In the very beginning of his introduction to his book, Roget emphasizes that what makes his book unique and helpful is that the words are not arranged alphabetically, like a Dictionary, but “according to the ideas which they express.”

“The purpose of an ordinary Dictionary,” Roget wrote, “is to simply explain the meaning of the words.” After you look up the word, you are given the idea the word is supposed to convey.

The Thesaurus is supposed to work in the opposite direction: you start with an idea, and then you find the words to express it.

To put it another way: a dictionary turns words into ideas and and thesaurus turns ideas into words.

“We tend to think of a thesaurus as a collection of synonyms and antonyms,” writes Roget’s biographer, Joshua Kendell. “But Roget’s is essentially a reverse dictionary. With a dictionary, the user looks up a word to find its meaning. With Roget’s, the user starts with an idea and then keeps flipping through the book until he finds the word that best expresses it.”

What this means is that if you organize a thesaurus alphabetically (which is exactly what publishers have been doing for the past hundred years or so) you essentially destroy everything truly unique about the book. You’re left with a synonym dictionary, which is convenient and useful, sure, but doesn't really clue you in on the matrix of meanings presented by organizing words by category.

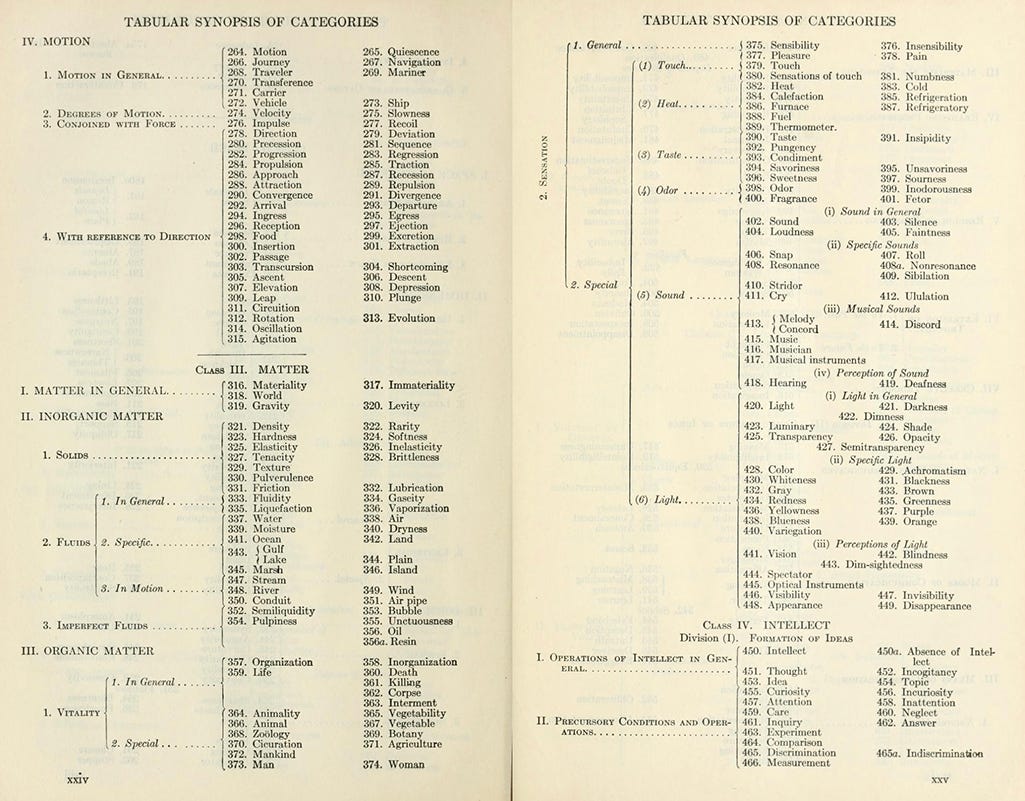

Also not good: since around 1962, publishers have abandoned the side-by-side layout of opposing categories which Roget insisted on as a visual representation of the opposing ideas. “By carrying the eye from the one to the other,” Roget wrote, “the inquirer may often discover forms of expression, of which he may avail himself advantageously.”

So instead of “Good” and “Evil” literally facing off against each other on the page as in this 1911 edition:

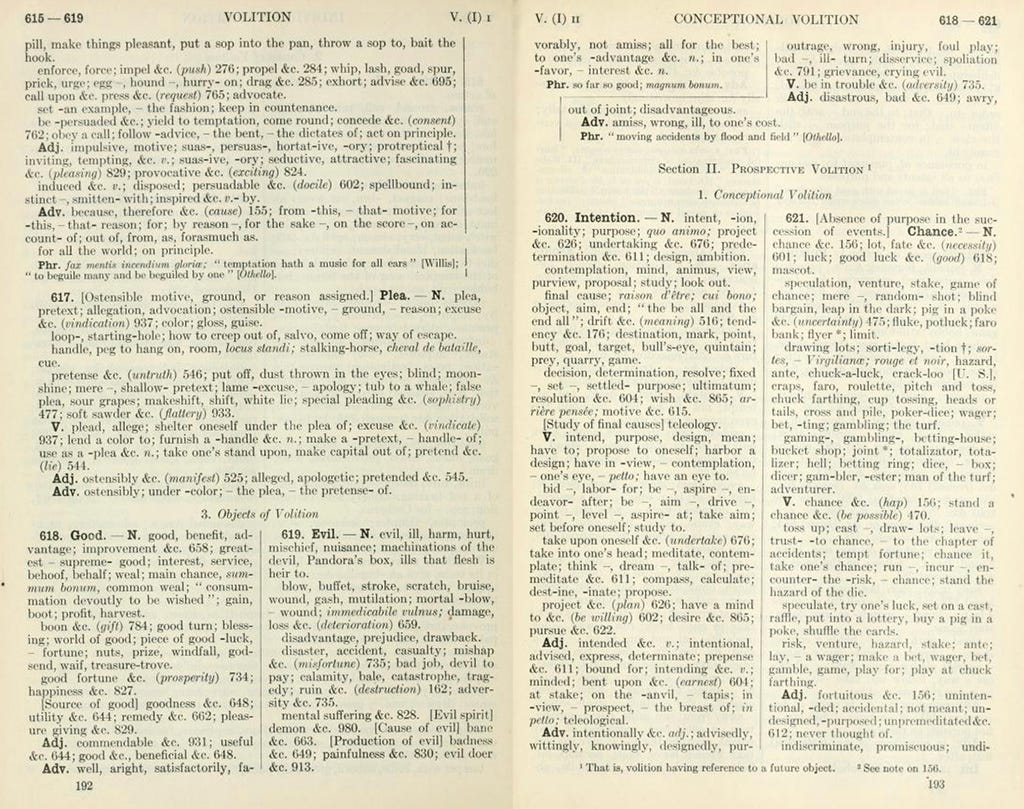

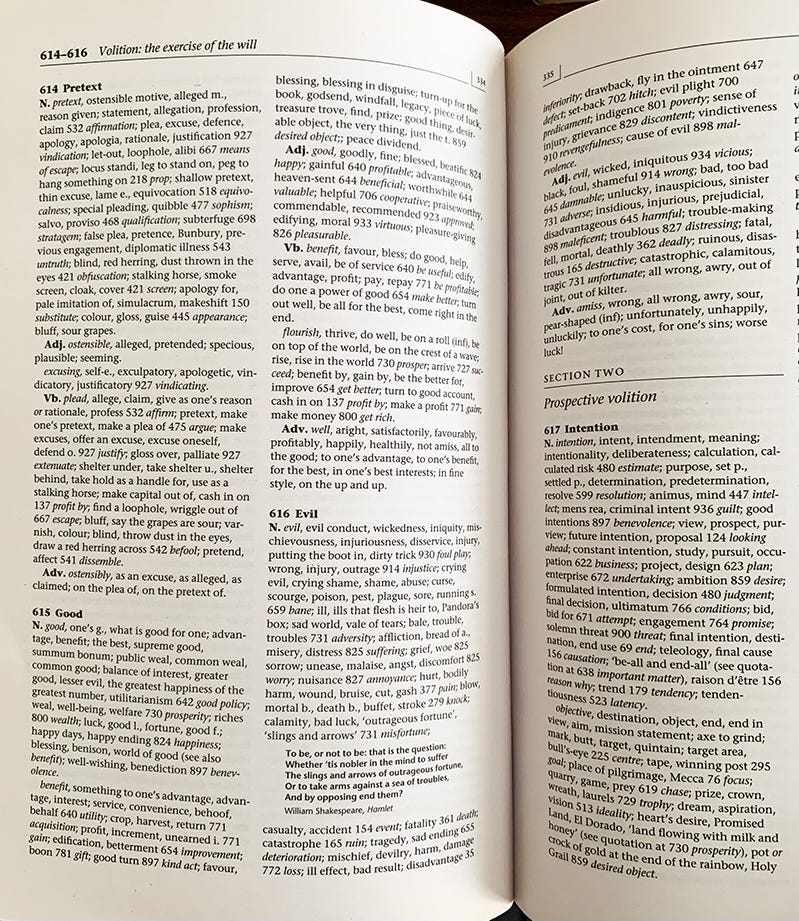

You get “Evil” simply following “Good” in the 2019 edition:

Maybe this doesn’t bother you, but for me, it’s one example of one of the many ways book design is actually getting less sophisticated over time. (To be fair, Roget’s printers in the 19th century complained about his columns. And I’m sure it’s way less of an editorial nightmare and far easier in page design software to make the whole text linear and flow it into two columns, regardless of how they correspond.)

I fear I have gone on too long. Many of you, particularly those of an older generation, are probably familiar with Roget’s book in its original organization, but for those of you, like me, who have only come across the thesaurus in alphabetical format — seek out a categorical one! It might blow your mind. (The 1911 edition is out-of-copyright and available for browsing and download at the Internet Archive.)

“Every workman in the exercise of his art should be provided with proper implements,” wrote Roget. I feel like I’ve discovered a powerful new tool. I think Roget’s Thesaurus will be useful to me not just when I need to swap a word for another word, but when I’m grappling with ideas I don’t have words for yet. From now on, I’ll be consulting the Thesaurus not just while I’m writing, but before I write.

Now I want to hear what you think. Do you have a favorite thesaurus or other reference book? Tell us in the comments:

xoxo,

Austin

PS. Three sources I found helpful to this writing: Dr. L. John Old’s lecture, “After 150 years: The Topicality of Roget’s Thesaurus,” the introduction to Joshua Kendell’s The Man Who Made Lists: Love, Death, Madness, and the Creation of Roget's Thesaurus, and Jen Bryan’s The Right Word: Roget and His Thesaurus, a picture book beautifully illustrated by Melissa Sweet:

I bet most of us aired our frustration when we entered a “vicious circle.” But I was OLD before I discovered there was a such a thing as a “virtuous circle”—to me, it’s like you do good and pay it forward to create a circle of good. Once you have the vocabulary for it, you tend to believe in it and try to promote the virtuous circle.

Likewise, the German word “schadenfreude.” How many of us secretly practiced this only to learn we weren’t the only one? I just recently learned there’s the opposite! It’s freudenfreude. It means to take pleasure in the good that happens to others. It’s been thrilling to practice this actively and double the joy that is in the universe. I believe that we are all One. Wish good upon others and you’re actually wishing good upon yourself. How cool is that!!? That’s what I’m going to cultivate. The reap what you have sown idea from that five letter word book.

My favourite reference book is Roget's for sure. I had a copy for my 18th birthday and I used it through my twenties as a thesaurus. But the best application I found for it was unexpected: it came in super handy when I was breastfeeding; I used to rest my feet on it at the sofa as a little footstool. It was the perfect height to support my posture - and as a result is now very scuffed and well-loved!